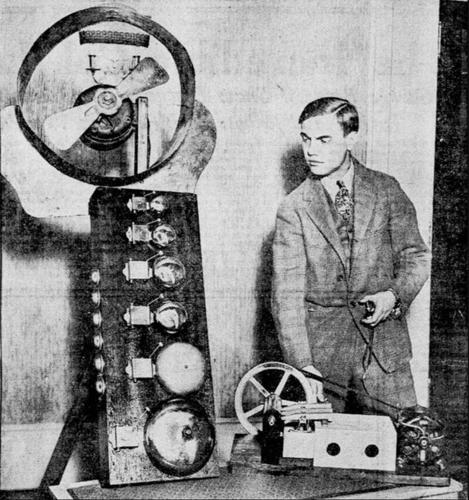

Composer George Antheil with a noise-making machine used for 'Ballet Mécanique.'

When “Ballet Mécanique” was given its world premiere in Paris in 1926, the onslaught of synchronized player pianos, airplane propellers, sirens, electric bells, and percussion whipped the audience into an opening night frenzy. Some of the most prominent artists of the day began to throttle one another and rain fists upon their neighbors’ heads. Even in a city jaded by musical scandals (“The Rite of Spring” was unveiled there in 1913, sparking surely classical music’s most-discussed riot), “Ballet Mécanique” was something special.

The composer was George Antheil (pronounced “ANN-tile”), born in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1900. Antheil went on to pursue an unusually varied career, but he never could live down this masterpiece of the Machine Age. It is not for nothing that he titled his autobiography “Bad Boy of Music.”

This week, Trenton’s Bad Boy will make good when he is embraced by his hometown orchestra, the Capital Philharmonic of New Jersey, under circumstances that will not soon be forgotten.

In a prime example of form following function, “Ballet Mécanique” will be the centerpiece of a kind of industrial vaudeville to be held at the Roebling Machine Shop, 675 South Clinton Avenue, in Trenton, on Saturday, April 20, at 7:30 p.m.

Also on the program will be equally striking works by John Cage and Lou Harrison.

Don’t expect a stereotypical classical music concert, a meditative evening of communion with lofty creative geniuses of yore. Visceral novelties will abound, not only in the unusual instrumentation required for performance of the individual pieces, but also in the context in which they’ll be presented.

“I’ve never been able to mount a concert quite like this,” says the music director of the Capital Philharmonic, Daniel Spalding. “All the pieces have connotations of industry and factories and things like that. The John Cage has five graduated thunder sheets. So you get sheet metal hanging up on these big racks. The Harrison uses coffee cans. There all kinds of interesting instruments. Gongs and cymbals, of course, and all kinds of stuff. I’m excited about it. But it took a lot of planning!”

The orchestra’s musicians will be joined by the Plenty Pepper Steel Band, a group formed in 2015 to celebrate the musical traditions of Trinidad and Tobago (see Susan Van Dongen’s article, page 7), and Trenton Circus Squad, a nonprofit afterschool program that introduces young people to the circus arts. These include unicycling, aerial and acrobatic feats, juggling, and clowning.

“When people come into the building, we’ll have the steel band playing,” Spalding says. “What could be more appropriate than big steel barrels to go with the factory? Members of the band will also augment the other players in some of the other pieces, especially ‘Ballet Mécanique,’ which requires 12 percussionists. Trenton Circus Squad will come in, and they’ll juggle and entertain the crowds.”

Since every piece will require a special set-up, Spalding says that there will be what he calls “moving music” — additional musical interludes to keep everyone engaged. These will include George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm” played on the marimba by Capital Philharmonic percussionist Greg Giannascoli.

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Concerto for Four Harpsichords will be performed, in Spalding’s arrangement for four pianos and percussion, with the string parts played on xylophones. “Because how often do you get four pianos together?” he quips.

John Cage’s “First Construction in Metal” will include parts for five graduated thunder sheets, water gongs, muted brake drums, cowbells, and Japanese temple gongs. Capital Philharmonic concertmaster Nina Vieru will lend a touch of lyricism to Lou Harrison’s Concerto for Violin and Percussion Orchestra, which will include a contrabass (on its side, the strings played by sticks), two washtubs, two resonated clock coil chimes, six graduated coffee cans, pipes, and six suspended flower pots.

The program will open with Spalding’s own percussion contribution, “Overture to Industry.” (Last year, Arabesque Recordings released an album of his original compositions, “Daniel Spalding’s Early Works,” played by the Philadelphia Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra.)

The Capital Philharmonic’s performance will mark the centenary of “Ballet Mécanique,” which was originally conceived in 1924 to accompany a film by modernist painter Fernand Léger.

On Saturday, the work will be heard in its 1953 revision for four pianos and percussion, with sirens.

“It’s really the only version you can mount without 16 player pianos, which only really works if they’re hooked up to computers,” Spalding says. “This 1953 version is more compact. The pianos are really treated more like percussion instruments. It’s really cool.”

An enormous painted backdrop will stand in for the airplane propellers, the sounds of which will be reproduced digitally.

“We’re not going to have real airplane engines,” Spalding adds with a laugh.

In its heyday, the Roebling Company was recognized internationally for its production of steel wire rope employed in the nation’s landmark suspension bridges, including the Brooklyn and George Washington Bridges in New York and the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. The industrial estate, established by John Roebling in 1848, also produced telephone and telegraph wire, elevator wire, lightning rods, and railway cables.

The red brick machine shop is where all of Roebling’s production machines were designed, built, and repaired. It is the oldest and best-preserved of the surviving structures in Roebling’s 45-acre complex. Constructed in 1890, the building was modified several times in the early 1900s. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1997 and now houses Trenton’s Museum of Contemporary Science.

A longtime Antheil champion, Spalding first discovered the score of “Ballet Mécanique” as a student at Northwestern University. Over the past 10 years of the Capital Philharmonic’s existence, he has programmed several other works by the composer, including his “Jazz Symphony,” the concert overture “McKonkey’s Ferry (Washington in Trenton),” and the ballet “Capital of the World,” which also calls for a flamenco dancer.

In 1999, he recorded “Ballet Mécanique” with the Philadelphia Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra (a group he founded in 1991, more than two decades before the establishment of the Capital Philharmonic) in the ballroom of the Trenton War Memorial. Several of the companion pieces were advertised as world premiere recordings. The album was released on the Naxos label and became an instant bestseller, both in England and the United States.

A second Antheil album followed on New World Records, featuring the Piano Concerto No. 2, the Serenade No. 2, and the ballet “Dreams,” which was originally choreographed by George Balanchine. The soloist in the concerto was Guy Livingston, another one of the composer’s champions. Livingston directed an Antheil festival in Trenton in 2004.

Spalding’s other recordings for Naxos include programs devoted to American composers Howard Hanson and Vittorio Giannini. Spalding’s wife, Gabriela Imreh, is highlighted in Giannini’s Piano Concerto.

George Antheil was a brilliantly gifted, multifaceted artist. He was also a colorful personality, a brazen eccentric prone to exaggerating the truth — though why that would be the case is anyone’s guess, as the truth often turned out to be quite enough.

Antheil climbing to his apartment above Shakespeare and Company in Paris.

In his lifetime, he rubbed shoulders with Igor Stravinsky, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Leopold Stokowski. In Paris, he kept an apartment above Sylvia Beach’s bookshop, Shakespeare and Company. He achieved notoriety for music that inspired audiences to violence or intimidated them into stunned silence. His early piano works emulated a mechanized world gone mad. They inspired such a visceral response from audiences that the composer took to carrying a pistol in a silk holster sewn into his jacket. This he would ostentatiously remove and place atop the piano before commencing his recitals.

A contemporary of Aaron Copland and George Gershwin, he later embraced a more conservative sound, writing symphonies and Hollywood film scores. He also wrote mysteries and news articles and an advice column for the lovelorn. A treatise on endocrinology endeared him to actress Hedy Lamarr, with whom he developed a scientific invention to aid in the Allied war effort.

In addition to being one of the screen goddesses of her day, Lamarr possessed an extraordinary scientific curiosity. Furthermore, she had learned a thing or two about weaponry from her ex-husband, who was an arms dealer. Antheil brought to the table an understanding of the inner workings of the piano, with its 88 keys, and together they devised a frequency-hopping system that would have prevented the Nazis from jamming radio-controlled Allied torpedoes.

The war ended before the military realized its true value, but Lamarr and Antheil, neither of whom ever saw a cent for their patent, unwittingly anticipated modern wireless technology.

Antheil died of a heart attack at the age of 59. Radio personality Jean Shepherd, whose own memory is kept alive through annual telecasts of “A Christmas Story” (based on his autobiographical reminiscences), adored him, and incorporated his music into his radio shows. After Antheil’s death, Shepherd delivered an on-air eulogy to the composer. For his music bed, he used “Ballet Mécanique.”

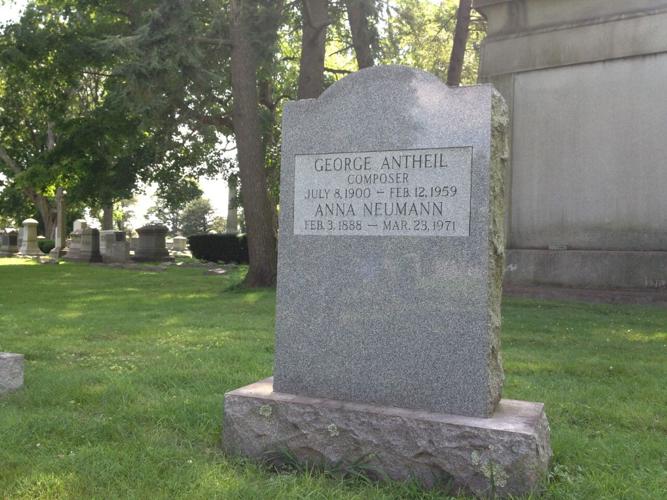

Antheil’s grave in Trenton’s Riverview Cemetery.

The greatest composer of classical music Trenton ever produced is buried in Riverview Cemetery, not far from the place of his birth.

“You never run out of stuff when you talk about George Antheil,” Spalding muses. “He was quite a guy. I wish I could have met him.”

For tickets and information, visit www.capitalphilharmonic.org.